From the minute coffee arrived

in Europe in the early 17th Century the robust brew won admirers

ranging from businessman Edward Lloyd to Pope Clemente VII.

|

| Morning coffee, Author's own image. |

Along with coffee came

the coffeehouse, an import from the Middle East, just like coffee itself.

Coffeehouses were cultural hubs attracted artists, businessmen, and intellectuals—all

drawn to the drink which drove away drowsiness. For a mere penny one could buy

a cup of coffee and gain admission to the coffeehouse, a place teaming with

characters ready to discuss the latest innovations in art, politics, and music.

These characters included intellectual giants like Isaac Newton, Abraham de

Moivre, John Dryden, and Johann Sebastian Bach. In addition to coffee and

conversation, coffeehouses hosted chess matches, scientific lectures,

mathematical consultation, and musical concerts.

Coffeehouse soon replaced

taverns as gathering places for conversation and business meetings as coffee

promotes intelligent thinking while alcohol promotes drunken babbling, bad

conversation, and bad business.

|

| Lloyd's Coffeehouse. A public domain image. {PD-1923} |

A coffeehouse in London

owned by Edward Lloyd was popular among mariners who would go there to do

business and insure their ships. Lloyd began creating lists of all the ships

represented by his customers, their cargo, and their schedules. Insurance

providers found these lists so useful that Lloyd’s coffeehouse became better

known for its marine insurance than its coffee! The coffeehouse transformed

into Lloyd’s of London, the famous insurance company which is still in

operation today.

Lloyd’s was not the only

coffeehouse to grow into a larger business. The London Stock Exchange,

Sotherby’s Auction House, and Christie’s Auction House all grew out of

coffeehouses. Even the Royal Society has its roots in the Oxford Coffee Club.

|

| Zimmermann's coffeehouse. A public domain image. {PD-1923} |

Johann Sebastian Bach

frequented Zimmermann’s coffeehouse in Leipzig, Germany, a gathering place for

local musicians. It’s no wonder the Bach was a coffee drinker given his hectic

schedule as a teacher, composer, conductor, and father of ten children. Bach

arranged and conducted weekly concerts performed by musicians from the collegium musicum at Zimmerman’s

coffeehouse for ten years.

Bach, being the

overachiever that he was, was not content only enjoying coffee and conducting

concerts at Zimmermann’s. Inspired by the delicious drink, Bach composed BWV 211,

better known as the Coffee Cantata. Bach is seen as a serious, cerebral

composer, but the Coffee Cantata shows that he had a lighter side. (Listen to

BWV 211 here, and read an English translation of the text here.)

|

| Author's own image. |

Christian Friedrich

Henrici, also known as Picander, a poet and librettist, collaborated with Bach

on the text for BWV 211 which recounts the story of a young coffee drinker,

Liesgen, and her father Schlendrian (his name literally translates to “lazy

bones”). Schlendrian who vehemently opposes his daughters coffee habit. Liesgen

agrees to give up most pleasures in life, like new clothes and the view from

her window, if she can keep drinking coffee. But when her father threatens to

prevent her from getting a husband, Liesgen gives in and agrees to give up

coffee—or so she says.

Here’s where Picander

original libretto ends, but Bach was not about to finish his cantata with

Liesgen’s defeat. Bach had Picander add a second half to the story in which

Liesgen goes behind her father’s back and forms a contract with her future

husband which will allow her to drink all the coffee she wants. In the end,

Schlendrian admits that it is impossible to keep women from their coffee.

Despite their love of

coffee, Baroque women, aside from disreputable “coffee-trollops,” were not

allowed in coffeehouses. However, like Liesgen, they were not about to let

anything keep them from enjoying coffee on their own. Women formed coffee

societies where they met in one another’s homes to drink coffee and talk.

|

| A public domain image. {PD-1923} |

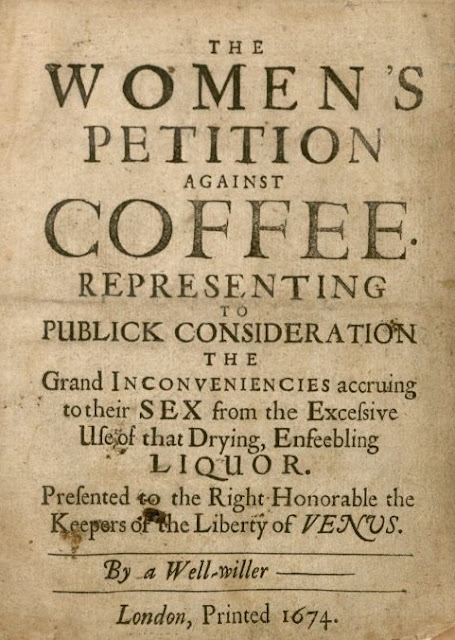

English women were not

satisfied with coffee societies and became increasingly irritated with men and

their coffeehouses. In 1674 British women produced the Women’s Petition Against

Coffee where they insisted that coffee made men weak. In their words: “Some of

our Sots pretend tippling of this boiled Soot cures them of being Drunk; but we

have reason rather to conclude it makes them so, because we find them not able

to stand after it[.]”(Read the full text of the Women’s Petition Against Coffee

here.)

Pietist preachers

insisted that coffee drinking was as evil as using inappropriate music in church.

This jab may have been particularly aimed at Bach who was a known coffee

drinker and who was considered to make radical music choices for Sunday’s

service.

Johann Heinrich Zedler

praised the energizing effect of coffee, but mentioned its drawbacks which

included weakness and a yellow complexion. Others complained that drinking

coffee wasted time and distracted people from their work.

Charles II, king of

England, opposed coffee and the progressive thinking promoted by coffeehouses.

He was concerned the coffee drinkers might rebel against his noble rule.

Charles’ answer to this problem was to ban coffeehouses. This outraged his

citizens and instigated more resistance to Charles’ rule than coffee drinking

did. The British government was forced to withdraw the ban after a mere eleven

days.

The Baroque era was the

golden age for coffee in Europe. After the 1700s the aristocrats began to drink

the next popular drink, tea, and the common people soon followed. I’m normally

a tea drinker myself, but while writing this post I drank a cup of coffee and

enjoyed it almost as much as Liesgen did.

No comments:

Post a Comment